Homelessness in Australia - The causes and potential solutions

There is no doubt, Australia’s homelessness problem has worsened.

In a post covid setting, rapidly rising house prices have combined with a rental affordability and property scarcity crisis to displace those who are unable to afford, find or secure a rental property. Part of the problem is that landlords are able to earn more income from short-term holiday letting their investment properties rather than renting to a long term local.

As inflation continues to rise, interest rates have followed. This has combined with the aftermath of natural disasters that have ravaged communities across Australia over the last two years. Bushfires and major flood events have impacted families enormously, destroyed property and affected infrastructure.

This post is not an attempt to map out all aspects of the homelessness issue in Australia; nor does it attempt to solve it

My aim has been to understand some of the key factors involved, and highlight a few possible solutions that are being considered, proposed in important research or, better still, are being implemented.

As Dharma Care begins to plan the delivery of a local project to build a Manufactured Housing Estate (MHE) near Murwillumbah, it felt important to understand the various aspects of what causes homelessness and what solutions are appropriate.

You will read more on Dharma Care’s MHE project towards the end of this post.

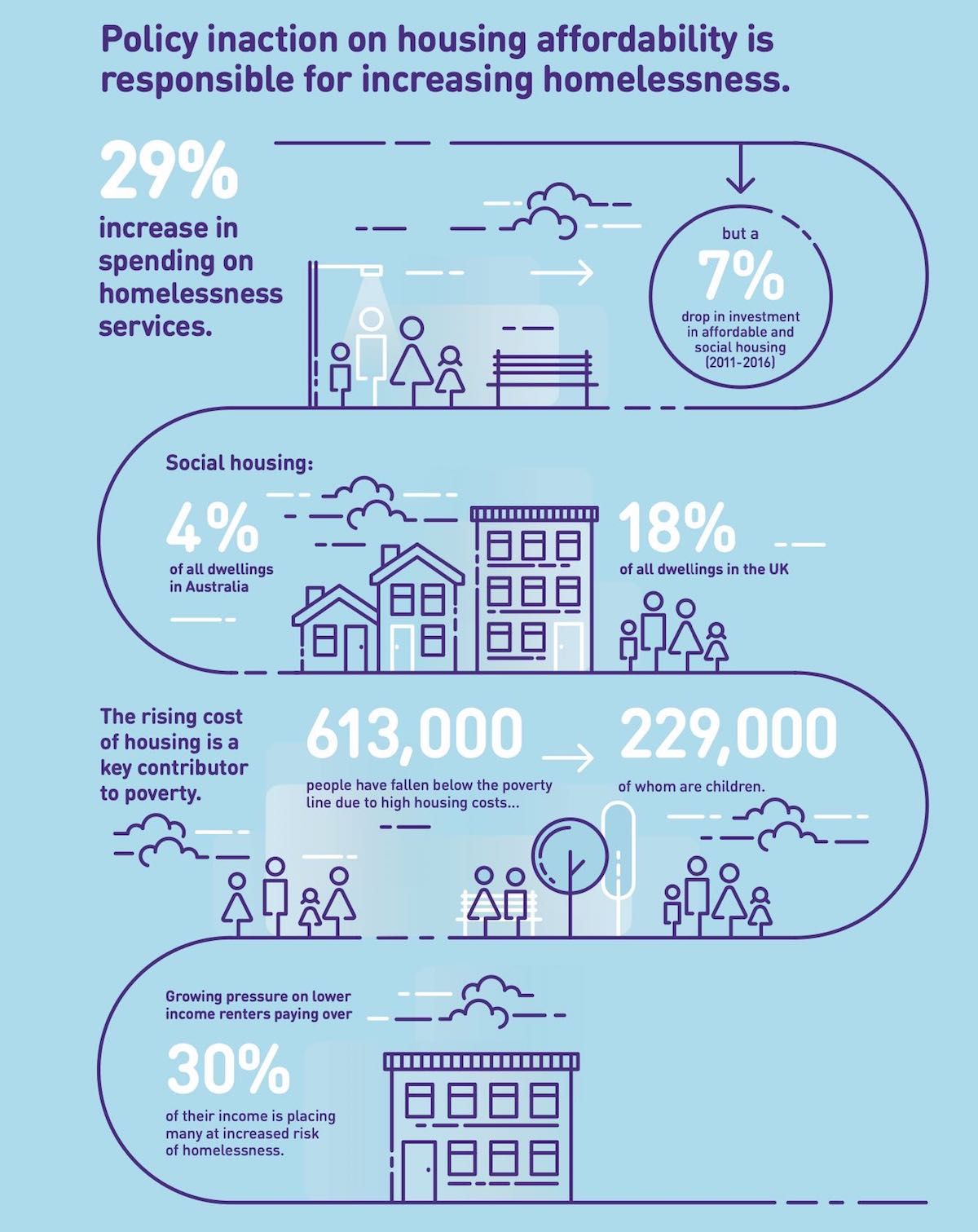

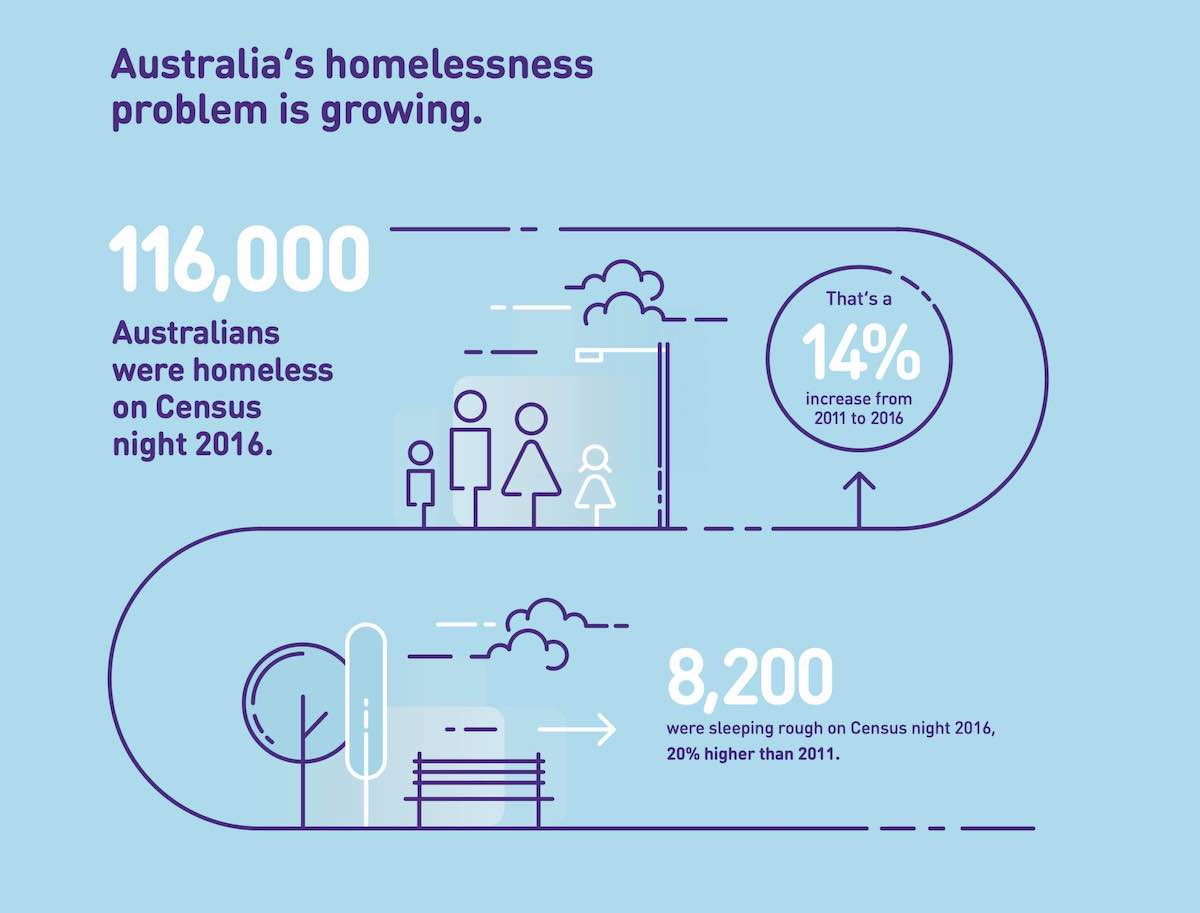

Australia’s homelessness problem is growing

It certainly is according to the The Australian Homelessness Monitor 2018, the first independent analysis examining the changes in the scale and nature of homelessness in Australia.

This analysis was inspired by the ground-breaking UK Homelessness Monitor project commissioned since 2011 by Crisis UK and funded by Crisis and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Launch Housing partnered with the University of NSW and the University of Queensland for this first of its kind authoritative insight into the current state of homelessness in Australia.

Drawing on the work of prominent UK researchers such as Fitzpatrick and colleagues who were involved with the original UK Homelessness Monitor, the report details the complex causes of homelessness, but also demonstrates that sound policies and programs can prevent people from experiencing, or continuing to experience, homelessness.

Drawing on statistical analysis, the report considers the consequences of the global financial crisis, the growing shortfall in affordable housing, decreases in welfare payments, higher rates of domestic and family violence, increases in older Australians experiencing homelessness, and many other difficulties people may face in trying to access or maintain a home.

Over the past five years, homelessness has increased nationally by 14%, and rough sleeping by 20%.

The past decade has also seen an 88% increase in those affected by overcrowding.

Why do people become homeless?

According to St Vincent de Paul Society, the main reasons for homelessness are:

Housing crisis – 40%

Family and domestic violence – 35%

Financial difficulties – 11%

Relationship or family breakdown – 5%

Mental health, physical illness or addiction – 2%.

Who are the homeless?

The Salvation Army highlights the increase in young people accessing help.

Youth homelessness statistics

- 6 in 10 (61%) homeless youth aged 12-18 years live in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings

- Over four in 10 (40%) young people aged 15-24 assisted by Specialist Homelessness Services in 2019-20 had a current mental health issue

- Of the children aged 15-17 presenting alone to Specialist Homelessness Services agencies in 2019-20, over 60% were female.

Another large group of Australians presenting to Specialist Homelessness Services include families with young children. In 2019-20, 3 in 10 clients were under the age of 18. This equates to over 85,000 children. Families with children may be sleeping in cars or temporarily with friends or family in what could be classed as a ‘severely’ crowded dwelling.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) argues that many Australians known to be at particular risk of homelessness include those who have experienced family and domestic violence, young people, children in care and under protection orders, Indigenous Australians, people leaving health or social care arrangements, and Australians aged 55 or older.

What is required to solve the homelessness problem?

It is clear from the above statistics that the range of issues that cause homelessness and the solutions to address them are complex.

Real long-term solutions will require a combined approach involving Federal and State government agencies and providers, NFP / NGOs, community groups, and the private business sector working together.

Mission Australia Executive, Ben Carblis, makes the following plea to get these problems under control.

“It’s unacceptable that people and families across the country are facing enormous pressures with escalating rental stress and very limited availability of affordable places to rent, which is pushing them to the verge of homelessness.

Finding an affordable home to rent has never been so difficult. Many are heading into 2022 already homeless – often unexpectedly – because there aren’t enough accommodation options to go around for everyone who needs them.

Our dual housing and homelessness crisis is a blight on our country. With so much human suffering, the question remains: why isn’t more being done to repair and invest in Australia’s housing system?

This crisis demands the Federal Government take the reins of a national plan to end homelessness in Australia which focuses on long-term investment to address the stark shortage of social and affordable homes.”

A fantastic report released in November 2021 titled Ending Homelessness In Australia by the Centre for Social Impact, at the Business School of The University of Western Australia, was prepared by Paul Flatau, Leanne Lester, Ami Seivwright, Renee Teal, Jessica Dobrovic, Shannen Vallesi, Chris Hartley and Zoe Callis.

The report proposes compelling new directions for solving many of these homelessness issues.

Their analysis of the last decade of evidence from the Advance to Zero database (2010-2020) reveals the high level of need that exists among those sleeping rough with many experiencing long periods of homelessness. There is a need for a supportive housing model for those seeking to access permanent, safe, and affordable housing. The analysis further demonstrates the role of key drivers of homelessness and the need to address these drivers and turn off the tap into homelessness.

The report argues homelessness is a complex problem and, if we are to end it, we need to understand and engage all the levers available to us (whether they’re currently being used or not).

It proposes five key actions to end homelessness in Australia.

- Leadership and proactivity at the Australian Government level and a national end homelessness strategy applying across the states and territories.

- An increase in the supply of social and affordable housing directed to an end homelessness goal.

- Comprehensive application of Housing First programs linked to supportive housing for those entering permanent housing with long histories of homelessness and high health and other needs.

- Targeted prevention and early intervention programs to turn off the tap of entry into homelessness which address the underlying drivers of homelessness.

- Supportive systems and programs which build the enablers of an end homelessness program: advocacy, commitment, and resource flow to ending homelessness; effective service integration; culturally safe and appropriate service delivery including expansion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-led and controlled services to help address high rates of homelessness in their communities; and improving data quality, evaluation and research around ending homelessness in Australia.

Northern NSW region

Dharma Care has its head office near Murwillumbah in northern NSW. Our region is continuing to recover from a major flooding event in February and March 2022.

There are now an estimated 3,800 homes deemed unliveable on the NSW north coast according to North Coast Community Housing CEO John McKenna. He says they have been lobbying all levels of government to improve the situation in the area for a decade.

“We already had a housing crisis here where four of our local government areas here had declared housing emergencies before the flood,” Mr McKenna said. This has made what was already a tough situation even harder for many in our community.

Homelessness NSW has released a joint statement with NCOSS, CHIA NSW and ACHIA calling on the NSW Government to fund a significant and immediate housing recovery package to address both the short term and long-term impact of the floods in NSW with a request to:

- Establish immediate temporary housing options for people on low incomes;

- Prioritise the rebuilding of existing social housing affected by the floods;

- Invest in additional social and affordable housing to address the critical shortage of housing in the flood impacted areas; and

- Make recovery grants immediately available to local community housing, Aboriginal and homelessness services to assist people made homeless as a result of the floods.

Recent news headlines really show the impact and divide in the local community over the rapidly rising house prices and rental affordability: “The billionaires are pushing the millionaires out of Byron.” and Hollywood and homelessness: the two sides of Byron Bay.

During the past 18 months, the town and nearby villages that form part of Byron shire have seen an unprecedented rise in housing inequality. Between June and December last year, the average apartment rental price went up by 33%, while the house rental price increased by 66%. Over the course of the year, house prices rose 37%, as people left cities to work remotely.

Rents jumped 35 per cent between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, while the number of Airbnb properties as a percentage of the rental market increased from 40.4 percent to 41.4 percent. The average of these Airbnb properties in Byron is occupied for just over two months of the year, and more than half are owned by hosts with multiple listings.

A spotlight on solutions

It is now time to look at some of the solutions that are out there and are working.

End Street Sleeping Collaboration

End Street Sleeping Collaboration is a community initiative whose goal is to halve rough sleeping across NSW by 2025 as part of an international movement to end rough sleeping.

The Collaboration uses the proven methodology of the Institute of Global Homelessness (IGH) that works on solving two problems simultaneously. It:

- gives front-line caseworkers the information they need to coordinate services to place individuals in secure housing with the appropriate wrap-around services; and

- gives government and NGOs the evidence they need to show where the health, social services, justice and care systems are failing so that these problems can be fixed and in the future others don’t enter into street sleeping.

The Collaboration has been established under a Joint Commitment between the Institute of Global Homelessness, the NSW State Government, and the sector’s largest homelessness NGOs.ness

CEO Sleep Out – St Vincent De Paul Society

I took part in the CEO Sleepout many years ago in Brisbane. The event raises money for St Vincent de Paul Society, and raises awareness of the growing issue of homelessness. It challenges business and community leaders to sleep rough for one night to raise funds to combat the issue.

On 23 June 2022, leaders in business, community and government again slept without shelter on one of the longest nights of the year to help change the lives of Australians experiencing homelessness.

In 2021, the Sleepout raised $9.3 million dollars to help break the cycle of homelessness and poverty in Australia.

Social futures call for investment and planning rule changes

In our area Social Futures is calling for the following changes.

- More investment in social housing, targeted to areas with acute housing shortages. This will take pressure off the over-heated private market.

- Amendments to state planning and land tax rules to create incentives for affordable housing to be included in new developments.

- Reform to NSW tenancy laws and regulations to remove no-grounds terminations, and ensure rent increases are proportionate and fair, and encourage longer-term leases.

- Prioritisation of social and affordable housing delivery on appropriate unused government land.

- Creation of a housing innovation fund to support not-for-profit organisations to deliver social housing that meets community need, including small-scale housing for one and two-person households.

- Increased funding to homelessness support organisations so they can intervene early and support people at-risk of homelessness.

Community project – Brisbane Zero Campaign

The Brisbane Zero Campaign is a community-based project to build public support for ending homelessness.

Reaching housing targets is a great start, but with an increasing homeless population, Brisbane Zero embraces Functional Zero as a more pragmatic approach to the problem. Zero for them means knowing people are going to be homeless – but doing what we can to ensure it is rare, brief and non-recurring. To achieve this goal, the campaign lists four key focus areas.

Real time visibility on the homeless community through establishing a quality By-Name List

They work with and train local communities to produce quality data to track the progress of successfully housing people. By tracking who is rough sleeping in our streets, parks and cars and what their needs are, communities can better understand homeless people and get to know them by name, connecting them with the right resources and providing better solutions.

Advocating for an increased supply of affordable (and permanent) housing

By lining up more affordable, permanent housing options, this means more people have access to a home, and dignity.

Providing ongoing housing and support to those who need it most

Homelessness should be brief before being rapidly resolved. This means moving more people into housing and supporting them. We’re there every day for those who need assistance, and give them the housing, healthcare and support they need in order to stay housed.

Connecting people, health care services and community

Continuing to work collaboratively across organisations, health-care services, agencies and the community to ensure homelessness is rarely recurring and never a chronic event.

NCCH seeking 45 properties from landlords

“We can make a difference to the housing crisis immediately if local property investors agreed to convert their investment properties from short-term holiday let to the long-term rental market and rent direct to locals or, even better, to North Coast Community Housing”, said John McKenna, CEO of NCCH. “Today we are starting our drive to get as many as possible of those holiday lets back rented to locals”.

Fletcher Street Cottage – Byron Bay Hub for homeless support

Byron Bay Council’s Fletcher Street Cottage, a homeless hub in the middle of Byron Bay has been open for a few months and they are overrun with demand for services. The hub will help the increasing numbers of local people at risk of becoming homeless, as well as people already sleeping rough.

The hub is a collaboration between Council, the Byron Community Centre and Creative Capital, who are helping to fund the venture.

The Cottage will provide homelessness and related services with the option of a limited, well-managed drop-in centre. It will help people sleeping rough to easily access services, while ensuring that everybody feels safe.

The Cottage will help the services in our community that are working hard to respond to the increasing volume and complexities of issues for people sleeping rough.

Read about more of the other homelessness and housing affordability initiatives that Byron Shire Council are working on.

Dozens of tiny homes proposed for Sunshine Coast as housing crisis worsens

A builder leading a social housing project in the Sunshine Coast hinterland has described the region’s accommodation crisis as “scary” and says there needs to be more action on the ground. As a result: Now Noosa Council has accepted and are considering his application to build 34 small modular houses on a six-acre block at Cooroy as part of a private social housing endeavour.

Greg Phipps says tenants will not have bills to pay because the homes are self-sustainable

Support groups say as many as six people per day are seeking urgent help to find accommodation

Greg Phipps has been building modular homes since 2007.

Manufactured Housing Estates – What are MHEs?

According to the 60 Plus Club: “Over the last few decades the manufactured housing industry within Australia has progressively transformed from a primarily holiday accommodation caravan park setting to an increasingly diversified mix of affordable permanent housing.”

MHEs get their name from the requirement that their homes are manufactured and can be relocated. Many manufactured homes are now indistinguishable from an ordinary home.

The MHE resident owns their own manufactured home on land rented from the estate owner. They are, therefore, simultaneously a homeowner and a tenant of the land on which it sits. The MHE resident has access to an attractive communal lifestyle with facilities such as landscaped areas, swimming pools and other facilities not available to the normal homeowner.

This model provides a sense of security through home ownership but also enables access to government Home Care Packages and the comfort of “ageing in place”. Home Care Packages are increasingly the federal government’s preferred form of support for the elderly. Planning regulations also allow the building of an infirmary on site for those in need of more advanced care.

MHEs create the possibility of modest capital gains when the home is sold. These gains may not be as great as those from a normal home because the resident does not own the land, the primary driver of capital gain. Tenancy of the land is obviously not as good as freehold ownership, but there are good protections for residents in the legislation, and surveys show these tenancies generally work well with few complaints. As tenants of the land, pensioners and low-income earners also have access to government Rental Assistance.

In addition to these advantages, the MHE model has less complicated legal arrangements compared to retirement villages that have high deferred management fees and exit fees, and limited opportunity for capital gain.

For MHE residents there are no rates, no stamp duty, no legal or body corporate fees. On average, MHE prices are set at around 65% of local median house prices compared to 75% for retirement village homes, although these percentages vary widely depending on the location and nature of the estate. This means, however, that they are a cheaper form of housing than a retirement village.

Benefits of MHE’s

- MHEs provide significant advantages to residents and developers over retirement villages.

- For residents: simpler legals, access to a range of price options, access to government rent and health care assistance, equivalent quality building, community facilities, greater perceived security, retention of capital gain, and ability to lease.

- For the developer: growing demand from an ageing population, a form of retirement housing and health care support that is becoming increasingly supported by government, a well-established and sound financial model that is supported by banks, stable and consistent cashflows, lower development costs, and potential capital gain on land and community facilities.

- Unlike retirement villages, MHEs have the advantage of being able to accommodate people of all ages and wealth profiles, and homes can be let if a resident is travelling.

Dharma Care is currently planning to bring a small MHE project close to Murwillumbah over the next few years and are open to partner contributions or support in the areas of infrastructure, town planning, council liaison, planning regulations, DA management, building and property services.

The MHE project we are launching is currently scoped to include the following aspects.

- It is a three-star development targeting low to middle income earners. This will not preclude someone purchasing a more expensive home.

- It promotes independent living in a safe and secure setting that has shared recreational facilities to encourage an active and diverse lifestyle.

- Its success (development and operation) will be dependent on transparent communication between stakeholders.

- It will provide approximately 44 2-bed homes plus 6 lower-cost bedsits or studios. This ratio may change as development is finalised.

- Rental accommodation will also be available with the aim of keeping rents within the NSW government’s guideline of below 30% of income.

Please reach out and contact us if you’d like to help, have specialist skills to offer, or want to be involved.

What else is important?

Having been excited by just a few handpicked examples of such a wide variety of important solutions and ideas that are being implemented, it does feel as though the homeless crisis is more likely to be met from enterprise and charities rather than from government initiatives.

For example, a post COVID work setting reduces the reliance and need for people to work physically together in corporate offices, and therefore many public buildings, churches, museums, art galleries and other empty buildings could easily meet the physical need of rough sleepers in cities and towns across Australia. We need to think outside the box.

To fully succeed though, any solution would need to be met with a unified service as well as support covering health, welfare, mental health support, rental and work search assistance, skills training, and overall program guidance to address the emotional needs of those that are most destitute and to address the various triggers and causes of homelessness.

Dharma Care hopes to play its part in solving the homelessness crisis in our area and perhaps find a model that can be replicated across Australia, particularly in regional communities.

I hope that in the next five years that at least rough sleeping can be ended. That would be a great start, wouldn’t it? What are your thoughts and what projects or other work is inspiring you? Will it be solved through community enterprise or governments policy and funding commitments?

We’d love to hear from you. You can contact us to let us know what you think or to help.

Article written and researched by Darren Sutton (Deputy CEO) and edited by Irwan Freeman Wyllie (CEO). Love. Dharma Care – July 2022.