"To be homeless is to endure the paradox of being exposed and invisible, of being at home everywhere and nowhere"

Having worked in more than 50 countries far beyond the tourist path, Livingston Armytage is an Australian photographer who takes the viewer behind the postcard view to illuminate and show the lives of others.

“My camera teaches me to see. In these photographs, I express what I have seen – both beautiful and ugly – for the viewer to contemplate. While pursuing beauty, I have found that it can often be found in unexpected places. I use the camera as a documentary tool to portray a reality that can affect the viewer in ways that words cannot. Some images are joyful: but others are confronting, even profoundly disturbing. My challenge is to capture these realities with balance, respect and integrity.”

Before becoming a photographer, Livingston worked as a lawyer spending many years building fairer societies in remote parts of Asia and the Pacific. In 2018, he was awarded the Order of Australia for his services to justice.

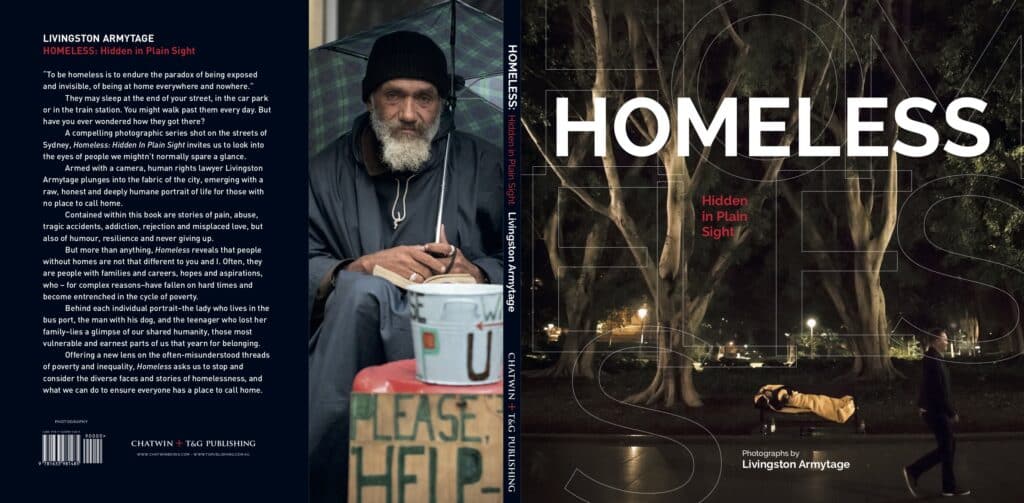

Livingston has been working for a number of years on a compelling photographic series, shot on the streets of Sydney, Australia, Homeless: Hidden in Plain Sight invites us to look into the eyes of people living without housing.

Armed with a camera, human rights lawyer Livingston Armytage plunges into the fabric of the city, emerging with a raw, honest, and deeply humane portrait of life for those with no place to call home. He aims to use photography as a documentary tool to portray a reality that can affect the viewer in ways that words cannot.

Fascinated by the work and the stories, we wanted to hear how this came to be and the effort required to capture such emotional human warmth in the beautiful people he met and their own unique stories.

How long did it take you do to shoot the images in your book and then release it ?

This has ended up being a three-year project. The shooting phase took much of the first year (2019), which was quite intensive for 4-5 months meeting and talking with homeless people across Sydney, ‘rough sleeping’ on the street in Newtown (which I found extremely challenging), doing late night shoots, and after midnight taking the ’night trains’ for the last stragglers home beyond Wollongong and returning with the early risers the following morning. Here I discovered a whole lifestyle of homeless people who shelter in the dry warm trains each night, and I witnessed the wordless compassion of the railway staff who let them do so.

The second year was spent finding commercial publishers which is always difficult – and doubly difficult for me to find two because Chatwin (US) would only publish with another local publisher (T&G) in Australia. And the third year was devoted to curating, formatting and editing the collection. This final phase was frustrating and sometimes agonising to me, as the artist, having to make unavoidable compromises with the publishers on how the work should be presented.

Overall, I believe they did a very professional job, and I’ve learned a lot from them, though I would have done it differently. I can’t explain why the publication process was so slow; none of my other 7 books have taken more than about 6 months to be published. Perhaps it is because printing photographs in full colour – which they have done extremely well – is very expensive. And certainly, Covid didn’t help!

Was there a process in getting to know individuals before you could then shoot such intimate moments with them?

It took some time for me to explore and find the best way to build trust, which ended up also being the simplest. I would explore the streets until I found a homeless person. After observing them for a while, I would find the right moment to approach and say “G’day, how’s your day?” (or some such).

If they were responsive – and they always were – I’d get down and sit beside them, rather than stand above them. After some chitchat, I might reach out to touch them, shake hands, touch their elbow, something to bridge the gap and show I was not afraid of catching social leprosy. I’d ask them to tell me their story. They would have been checking me out, of course.

They could see I was really listening, they always did. It wasn’t difficult for me to listen once I’d decided to reach out to them, though their hardship often shocked me. Then I’d ask if I could take their picture. Sometimes they became wary. I explained I wanted to publish a book showing their lives and telling their stories. There was never any problem; they always agreed.

Some explained that they were happy to share their stories if it would help others avoiding their plight. I was moved by their generosity. I had only one knock-back, and this was from a woman who wanted to keep her whereabouts secret from her family for security reasons. It’s really lonely being homeless, hidden in plain sight. Most people just walk past perhaps, like me, because they feel uncomfortable or perhaps because they think they are undeserving.

What is a key lesson you learned from people who are experiencing homelessness?

I have learned a lot photographing “Homeless”: obviously, I now really understand that this could happen to me, to anyone – no amount of education and hard work can actually guarantee it won’t.

I met executives, PhDs, professionals, old and young – all sorts. I have discovered that no one is immune from becoming homeless. There are many causes: child abuse, severe injury, psychosis, retrenchment, family estrangement – and of course always poverty. Drugs are a symptom, but rarely the cause. It’s quite frightening; all it takes is one trauma too many to shatter a life’s equilibrium. Many people I talked with remarked that they could never have imagined becoming homeless themselves.

I also learned that it’s a tough existence. Really tough! I tried ‘sleeping rough’ on the streets, and after just 24-hours had a gut-full. Instantly, I became invisible. People I would normally consider my peers walked past me without blinking. Others looked down with a mixture of pity and disgust. I felt judged and shunned.

Some of the homeless have been trapped in a churn of subsistence survival on the streets for over a decade. Anyone who thinks for one moment that the homeless are ‘dole bludgers’ has no idea of the reality. No one wants to be homeless. Ultimately, I have learned to respect them for their dignity, their resilience, their courage and their patience. The homeless reveal how we choose to see the state of our community. It is our humanity that is on display.

Were there any noticeable similarities or differences between the homeless people you got to know in different regions of Sydney?

I don’t really know. Some may move out of Sydney and go up north for the warmth of Coolangatta or beyond, but the situation may remain largely unchanged, though their costs are lower – that is, it may be more financially viable.

Did you observe different attitudes towards supporting homeless people in the CBD versus Newtown for example or other regional areas?

I’m not sure. I’d like to think that country folk may have more time to engage and more heart to be compassionate. But many homeless come from the country, so perhaps that’s not so. While most passers-by ignore the homeless, there are also always others who are compassionate, who do stop, share some moments of company and give them a sandwich or small change. The best experience that I heard was of a businessman giving a homeless woman $500. Others give meals.

When a stranger stopped and wordlessly gave me $5, it was like the lights were turned back on; it reduced me to tears.

What is the one thing that governments or people could do to help alleviate homelessness?

I have read of studies that document it would cost society more to leave the homeless until they require urgent police, paramedical and hospital attention costing many thousands’ than it would cost to allocate affordable housing. Sadly, there is evidently a hocus-pocus policy bias against providing ‘incentives’ to becoming homeless. In NSW the waiting list for affordable housing is as long as 15 years, which is grotesque for an affluent society.

It is my hope that this book may dispel some of these unreasoned prejudices.

What’s next for you?

I’m mulling over some other ideas now. As a development lawyer, I used to spend many years of my career travelling around the world to build fairer societies through advocacy and by helping the law courts delivery better justice.

In this book, I have grappled with some of the local injustices that surround us even in affluent societies like Sydney.

Homelessness is not our only social injustice. Time will tell.

Thank you to Livingston for taking the time to give us more insight into the book.

You can purchase the fantastically touching Homeless book now in Australia.

https://www.chatwinbooks.com/shop/homeless for International orders.

All proceeds from the book sale go to Matthew Talbot Hostel

Read more about the homeless crisis in Australia and what is being done to solve it, and you can support Dharma Care’s Emergency accommodation project in the Northern Rivers region.